What is consciousness?

The subject of consciousness has been an intriguing topic in the fields of science and philosophy for centuries. I am of the opinion that the most significant reason for the inherent motivation of human beings toward the concept of consciousness is that we intuitively perceive it as the unique characteristic of mankind; it is the closest scientific term to “soul”.

While numerous theories attempt to explain consciousness in scientific terminology, I would like to elaborate on my concept in accordance with Mark Solm’s theory, which I believe to be the most plausible explanation of what consciousness is. Before we get into my potentially dull and possibly recycled thoughts that smarter folks have likely already covered, let’s see what groundbreaking insights Mark Solms shared in his paper.

Consciousness is a biological imperative; it is the vehicle wherby complex organisms monitor and maintain their functional and structural integrity in unknown situations. (…) Specifically, increasing uncertainty in relation to any biological imperative jus is “bad” from the perspective of such an organism - indeed it is an existential crisis - while decreasing uncertainty just is “good”. (…) Consciousness adaptively determines which uncertainties must be felt (i.e., prioritized) in any given context. In short, consciousness is felt uncertainty.

The conceptual breakthrough reported here revolves around the insight that the residual error in each action/perception cycle is felt uncertainty - i.e., that each of the various categories of error possess affective “content” of their own.

The Markov blanket

In statistics, there is a concept called ‘Markov blanket’. It is defined as a subset that contains all the useful information to explain a given node. Being more specific in mathematics, a Markov blanket of variable \(Y\) in a random variable set \(\mathcal{S} = \{ X_1, \cdots,X_n \}\) will be any subset \(\mathcal{S}_1\) of \(\mathcal{S}\), conditioned on

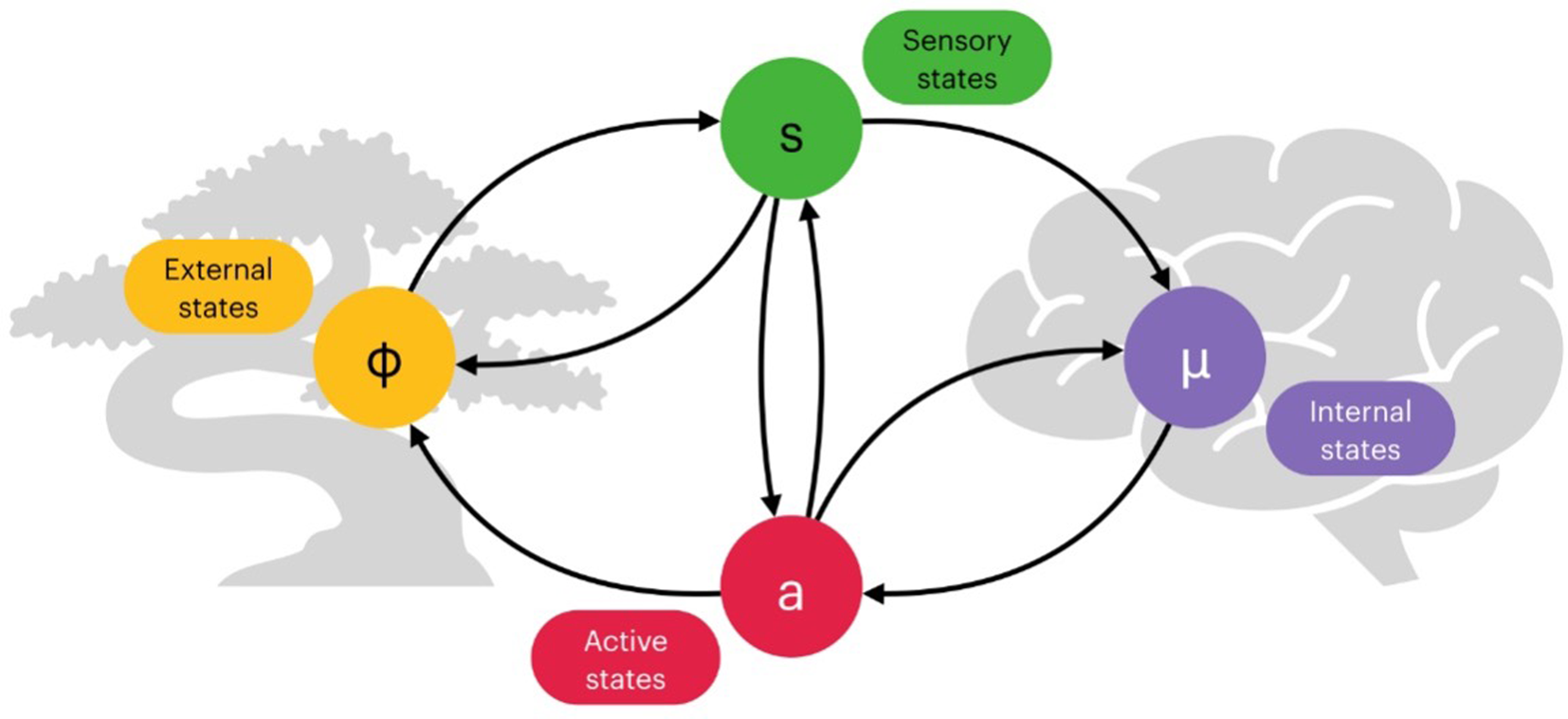

\[Y \perp\!\!\!\perp \mathcal{S} \backslash \mathcal{S}_1 | \mathcal{S}_1\]Our brain, however, is literally in a blanket of cells: the skin, bone, and muscles. The brain’s internal state (\(\mu\)) cannot directly interact with the true external state (\(\phi\)). We can only perceive the external world through sensory neurons and organs, and influence it through motor neurons and muscles.

The Markov blanket of the brain is thus defined as \(\mathcal{B} \in \{\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{a}\}\), where \(\mathbf{s}\) represents the sensory states and \(\mathbf{a}\) represents the active states of the individual. In conclusion,

\[\mu \perp\!\!\!\perp \phi | \mathcal{B}\]The brain’s dilemma

As mentioned above, according to Solms, our consciousness is the feeling of uncertainty. However, the brain’s objective is to reduce the expected surprise of all observation \(o\):

\[- \text{log } p(o) = - \text{log } \sum_{s} p(o, s)\]This leads us to a rather strange conclusion. If our consciousness is the feeling of uncertainty, and our brain is constantly striving to mimize that uncertainty, it’s as if our brain is trying to turn us into philosophical zomibes - unconscious, soulless beings. Ironically, what prevents this to happen are two major factors: the limited computational complexity of our brain and the fact that our brain is wrapped in a Markov blanket, preventing direct interaction with the external world. Therefore, prediction error and uncertainty inevitably arise.

While updating the internal world model is one strategy to reduce expected surprise, it is not the only option. We can also choose actions that lead us to states with less uncertainty. This brings us to the “dark-room problem.” To define it more specifically, I would like to quote from Karl Friston’s paper:

Alternatively but equally absurdly, agents should proceed directly to the least stimulating environment and stay there. That is to say, they should take up position in the nearest “dark room” and never move gain. This will always be the best way to reduce surprise for an agent that operates in the absence of an adaptively appropriate interpretation.

The paper I quoted refutes the dark-room problem, but it seems to me that this is actually what happens to many human beings as they get older. In the paper, Friston states:

This means a Dark-Room agent can only exist if there are embodied agents that can survive idefinitely in dark rooms. In short, Dark-Room agents can only exist if they can exist.

As humans, we steadily face challenging situations while working or studying, requiring us to adapt to the world. However, by the time you reach your 50s (or for some, their 60s), the external world starts to adapt to you more than you adapt to it. You no longer form dynamic new relationships, you may have accumulated enough wealth, and if you’ve had a steady career, your work might not be as challenging. Whether by choice or not, most people end up in this scenario. Consequently, you will live relatively more like a zombie compared to your early 20s or 30s.

So, what is my conclusion? Well, I suppose our brain was born to be lazy, and we cannot make it stop pushing us towards becoming zombies. However, by recognizing this as our fate, we can at least consciously acknowledge it and strive to challenge our brain as much as possible while we still can. Embracing activities that stimulate our mind, seeking new experiences, and staying curious can help us resist the pull towards mental stagnation. In doing so, we can maintain a sense of vitality and engagement with the world, making the most of our cognitive abilities throughout our lives.

References

[5] Solms, M. (2021). The hidden spring: A journey to the source of consciousness. Profile books.